Throughout most of the United States, one can find one or more soap plants occurring in the wild. Most of these were used by Native Americans, and at least one is considered an ornamental. In fact, there are quite a few plants which contain saponins, though not in volumes that make the plants useful as soap.

Soap plants are quite a bit different from the "old fashioned" soap that grandma used to make on the farm; those hard bars of soap that we associate with the pioneer days. Most of those soaps were made from a combination of animal fats (pig, cow, etc.) and lye (processed from wood ashes in the old days). Though that is a valuable skill, that's not what we're talking about here. We're speaking here of plants which are useful as a soap immediately, generally with very little processing.

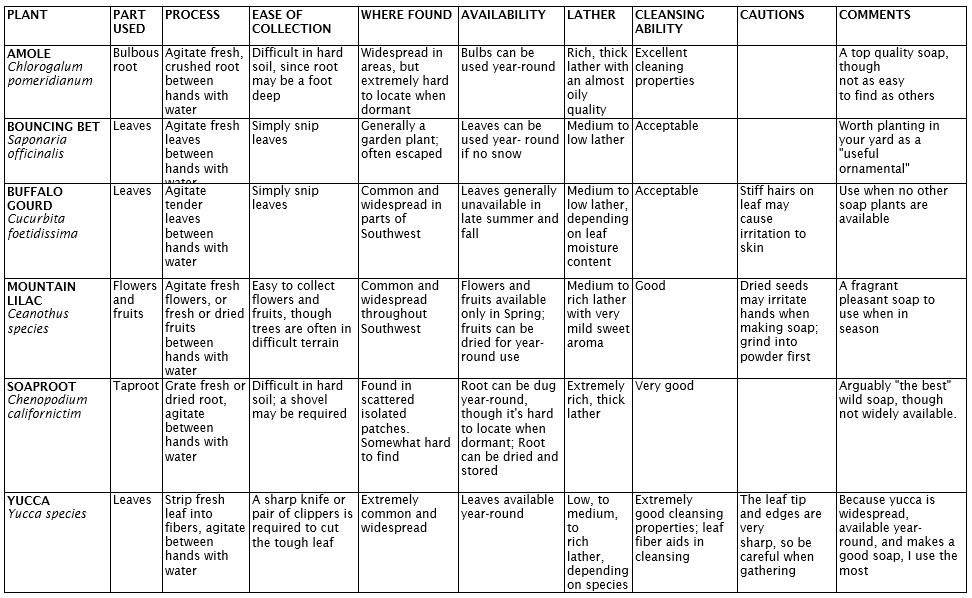

AMOLE

For example, there is the fairly widespread member of the lily family with the tennis ball size bulb referred to as amole (Chlorogalum pomeridianum). The long linear leaves measure a foot and longer, and they are wavy on their margins. When you dig down, sometimes up to a foot deep in hard soil, you'll find the bulb which is entirely covered in layers of brown fibers. I have seen useful brushes and whisk brooms made from a cluster of these fibers, which had been gathered and securely wrapped on one end with some cordage.

For the soap, you remove the brown fiber until you have the white bulb. It is formed in layers, just like an onion, and you'll find it sticky and soapy to handle. I have heard that some Indians ate these bulbs when roasted, but I always found that it was too much like eating soap! Perhaps I baked it wrong.

Take a few layers of the white bulbs, add water, and agitate between your hands. A rich lather results, which you can use to take a bath, wash your hair, wash your clothes, or clean your dog.

The bulbs can be dug year round if you know where to dig; when the plant is dormant in late fall and winter, there is only scant evidence to tell you that the bulbs are underground. Though the bulbs can be dug and dried for future use, the fresh bulb is superior.

BOUNCING BET

Bouncing Bet (Saponaria officinalis), also known as soapwort, is widespread. It is commonly planted as a garden plant for its pink flowers and occurs wild in some areas. It is an introduced plant with little history of use by Native Americans.

The leaves or the roots can be used, though I prefer to use the leaves simply because once you pull the root, the plant is gone. Bouncing Bet is made into soap by agitating the fresh leaves between your hands with water. The quality of lather varies, but it is worth knowing about should the plant grow abundantly in your area.

BUFFALO GOURD

Buffalo Gourd (Cucurbita foetidissima) is widely spread throughout the Southwestern United States, and can be found in remote deserts and in urban vacant lots. It also goes by such local names as coyote melon and calabazilla. This is an obvious relative of squash and pumpkins. The small orange-shaped gourds have been used as rattles by Southwestern Indians, though it makes a somewhat inferior rattle. The wandering vine arising from a huge underground root and the stiff leaves often stand upright. They have a unique aroma, and the leaves are covered with tiny rigid spines.

To make soap, pinch off a handful of the tender growing tips, or just the older leaves if that's all you can find. Add water and agitate between your hands; a green frothy lather results, which was used for washing clothes by Southwestern tribes. However, buffalo gourd is regarded by some as the soap of last resort since the tiny hairs may cause irritation to the skin.

MOUNTAIN LILAC

Mountain lilac (Ceanothus species) is a shrub to a small tree which is fairly common throughout the West. When you are hiking through chaparral, desert or mountain regions in the spring, you will notice a spot of white or blue or purple on the hillside or along the trail. There are many species which you can use for soap, and they also go by the names of buckbrush, snowbrush, and soapbloom. Since the botanical features of each species varies, the easiest way to determine if you have a mountain lilac is to take a handful of blossoms, add water, and rub between your hands. You'll get a good lather with a mild aroma if you have mountain lilac.

By late spring to early summer, the flower fall off and the tiny sticky green fruits develop. These too can be rubbed between the hands with water to make a good soap. The fruits can also be dried and then reconstituted later when soap is needed. I tried making soap with fruits that I had dried five years earlier. The fruits were very hard, so I first ground them up in my mortar and pestle. Then I added water, rubbed vigorously, and had soap. Not as good as from the fresh fruit, but soap, nevertheless.

SOAPROOT

One of the more interesting wild soaps is found in a genus of mostly edible and medicinal plants. Soaproot (Chenopodium californicum) is related to the nutritious lamb's quarter (C. album), the quinoa (C. quinoa), and epazote (C. ambrosiodes). In fact, you could cook the leaves of soaproot, change the water, and serve it as you would spinach. Most people looking at soaproot for the first time would think it was a type of lamb's quarter plant, but if they were observant, they'd know that something was different.

For one thing, soaproot has a large taproot, with a shape similar to a carrot or a large ginseng root. In hard soil, the root can be a foot deep and you'll need a good digging stick or a shovel to reach it.

To make soap, you first grate the root. You grate with your knife, or with a kitchen grater. Then you add water and rub between the hands to get a top quality, thick lather. It's a remarkable experience to produce that frothy lather from this plant. In most cases, it seems superior to even store-bought soaps, and it cleans quite well.

Native peoples often dried and stored this root for later use. When dry, it seems like a rock or a piece of hard wood. Yet, once grated and water added, you can still get a top-quality soap.

Unfortunately, soaproot seems to be found in scattered locations. It is possible that urban sprawl has destroyed much of this since it grows from its perennial root. I have never found large patches of soaproot, but only isolated patches. Therefore, you should only use small tap roots and leave the rest. I also take the seeds in summer and scatter them widely so more plants will grow. If you don't plan to take these precautions, I would suggest you leave this one alone entirely.

YUCCA

Finally, we come to the yucca plant. There are numerous species of yucca found widely, mostly throughout the Plains and Western states. They resemble big pin cushions, with their long, linear, needle-tipped leaves. In fact, yucca can truly be called the "grocery store" or the "hardware store" of the wild since this plant produces not only soap, but several good foods, tinder, top-quality fiber, sewing needles, and carrying cases or quivers from the mature, hollowed-out flower stalks.

Though the use of the root has been widely popularized, I have found that one need only cut one leaf to make soap. The job of digging up one yucca plant is considerable (not to mention possible legal ramifications), and to kill off a yucca just to wash your hands hardly seems justifiable. Besides, the soap from the leaf is perhaps 10 to 20% inferior to the soap from the root, but you get this leaf soap at perhaps 5% of the labor needed to dig up a root. So leave the roots alone. When you need soap, carefully cut off one leaf. Be very careful not to poke yourself with one of the sharp tips and not to slice your fingers on the very sharp edges of the leaf. To remove just one leaf I have found that garden hand clippers work well, as do the scissors of my Swiss Army knife. Then, snip off the sharp tip so you don't poke yourself. Then strip the leaf into fibers until you have a handful of very thin strands. Then, add water, agitate between your hands and you have a good quality soap.

Typically, I show my students how to twine rope or weave cord from the yucca fibers. We make a length of about two feet and then once everyone makes green soap, I tell them that they have nature's very own "Irish soap-on-a-rope." The rope is the soap, and one strand lasts about a weekend when you're in the wilds.

If you don't plan to venture into the wilds soon, you can get your very own "Irish soap-on-a-rope" - a two-foot strand of twined yucca, by sending $6 to Survival Services, P.O. Box 4183 4, Los Angeles, CA 90041.

Overall, yucca soap is the one I have used most often and in the most diverse of circumstances because the plant is widespread, easy to recognize, and is generally available for picking year-round. I even grow a few out back.

Soap is one of the many things we take for granted in our modern society. Most of use wouldn't have a clue how to make soap if suddenly we didn't have stores to go to. Fortunately in this case, nature provides us with many ready-to-use soaps. There is never an excuse to stay stinky and dirty in the outdoors. Soaps are everywhere!

STAY/CLEAN! A COMPARISON OF WILD SOAP PLANTS by Christopher Nyerges